The herd is thinning for us. This week we lost two members of the team.

My wife lost a long-ago, back in the nabe, friend, Bo. A great guy and talented musician from a neighborhood brimming with artistic achievement.

And just last night, we lost Uncle Petey. He wasn’t really our uncle. And he wasn’t really that old. But he was in bad shape for many years and, finally, he succumbed as the walls of poor health closed in.

He was a gentle Panda of a man who was like comfort food on two legs. In that sense, he was our “uncle.”

When I met the young woman who would become my wife, I was introduced to a world of energetic, creative men and women VERY unlike the meat-and-potatoes crew I grew up with, for I came of age in one of the bronxier sections of the Bronx. It was a place where you went to school, you joined the military, you got a steady job (Post Office, Board of Ed, Metro North — those would do just fine), got married, had kids, and retired at sixty-five. The “lives of quiet desperation” (thank you, Thoreau).

Not this crew. Nope. This new group was full of theater majors. At first, my opinion of theater majors was even lower than that of education majors. That is, “lazy, not-too-bright kids intent on securing their 2-S deferment and coasting for four years.”

I soon learned that these folks had energy, brains, ambition and talent up the wazoo. They pushed and pushed and became musicians, film directors, producers, and cinematographers, book publishers, disc jockeys, award-winning comedy writers, and actors, as was the case with Uncle Petey.

So many people give you the “woulda, coulda, shoulda” BS about their stillborn artistic endeavors. Here’s a typical one: “Yeah, I coulda written a book, but who has the time?”

Uncle Petey worked his butt off honing his craft, making connections, and pounding away on doors. It sounds corny but he was a “people person”, the kind of guy who methodically weaved webs of like-minded folks.

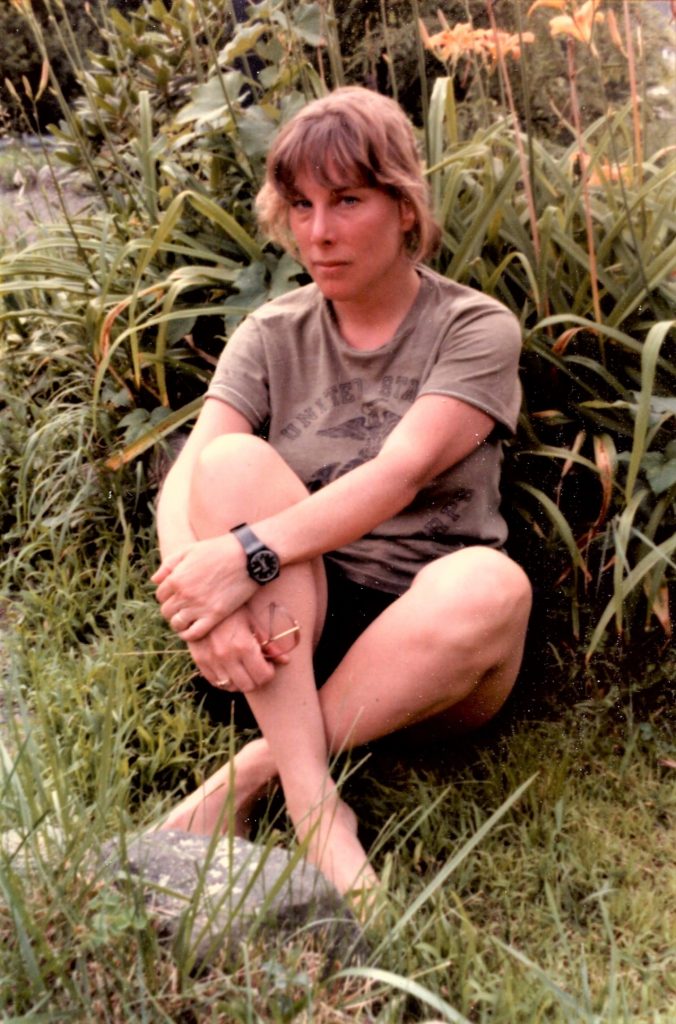

When I first met him and that post-collegiate crew, he held low stakes, nickel-and-dime, poker nights in his fan-conditioned, top floor walkup dump in the far East 90s, across from Knickerbocker Towers. It was Petey, me and my wife, and a rotating cast of their fellow theater majors.

I smile at the memory of those raucous nights. Lots of laughs in his cramped kitchen, back when we were in our twenties and giddy with good health. We barely had two nickels to rub together but our futures were before us. Through the adventures and achievements of Uncle Petey and that crowd, I found my own path out of my maze of mediocrity.

Uncle Petey was relentless in the pursuit of an acting career. No surprise, then, that over the years he got plenty of work. Work that took him to California where he became a beloved character actor who paired with bold-faced names. He got regular radio work. He came East and started a theater troupe. He earned his keep giving improv lessons to new generations of aspiring talent. From NYC, to London, to Indianapolis, a lot of people absorbed Uncle Petey’s passion and love of the craft.

Now he is gone but he’ll never be forgotten. He’s in my personal Hall of Fame, a pantheon of one-of-a-kind nut-balls, with others of blessed memory such as Uncle Kenny and Uncle Richie.

When I was a little kid, my sister and I would roll our eyes when my grandma would talk about life experiences and intone, in her heavy Yiddish accent, “…vell….as long as you have your health….” We’d snicker and laugh our bloody heads off.

Yeah, well who’s laughing now?

Alev hasholem, Uncle Petey. One of the good ones.